Politeness: A Comparative Study and Analysis

Politeness is a fundamental aspect of human communication, acting as the social lubricant that facilitates smooth and harmonious interactions. However, the specific norms, strategies, and expressions of politeness vary significantly across cultures and languages. A comparative study of politeness reveals how different societies navigate the complex balance between self-interest and social harmony.

Part 1: Theoretical Foundations of Politeness

To compare politeness, we first need a theoretical framework. Two influential theories are key to understanding this field.

1 Brown and Levinson's Politeness Theory

This is the most widely cited theory in linguistic politeness studies. It posits that speakers use politeness strategies to mitigate "face-threatening acts" (FTAs). "Face" refers to a person's public self-image, which comes in two types:

- Negative Face: The desire to be unimpeded, to have freedom of action, and not to be imposed upon.

- Positive Face: The desire to be approved of, appreciated, and validated by others.

Based on this, Brown and Levinson identified four main strategies for performing an FTA (e.g., making a request, giving an order, disagreeing):

- Bald on Record: Performing the act directly and efficiently, without any redress. This threatens the hearer's negative face most severely.

- Example: "Pass the salt." (In a context where directness is expected and acceptable).

- Positive Politeness: Redressing the threat to the hearer's positive face. This shows closeness, solidarity, and that you recognize the hearer's wants.

- Example: "Hey buddy, could you be a doll and pass the salt?"

- Negative Politeness: Redressing the threat to the hearer's negative face. This shows deference, acknowledges the imposition, and gives the hearer options.

- Example: "I'm sorry to bother you, but would you mind passing the salt when you have a moment?"

- Off-Record (Indirect): Performing the act in such a way that the speaker's intention is not clear. This is the most indirect strategy, giving the hearer maximum options to save face.

- Example: "This salt is a bit far from me." (Implies the request without stating it directly).

2 Leech's Politeness Principle

Leech's theory is based on a set of maxims that guide conversational cooperation. He argues that politeness is a principle that can sometimes override the Cooperative Principle. The key maxims are:

- Tact Maxim: Minimize cost to others, maximize benefit to others.

- Example: "Could you close the door?" (Better than: "Close the door.")

- Generosity Maxim: Minimize benefit to self, maximize cost to self.

- Example: "We must have another slice of cake." (Offering food).

- Modesty Maxim: Minimize praise of self, maximize dispraise of self.

- Example: "It was nothing." (In response to a compliment).

- Agreement Maxim: Minimize disagreement between self and other, maximize agreement between self and other.

- Example: "That's an interesting point, though I see it a little differently."

- Sympathy Maxim: Minimize antipathy between self and other, maximize sympathy between self and other.

- Example: "I'm so sorry to hear about your loss."

Part 2: A Comparative Analysis of Politeness Across Cultures

Cultural values deeply influence which politeness strategies are preferred. The most common distinction is between High-Context Cultures and Low-Context Cultures.

| Feature | High-Context Cultures (e.g., Japan, China, Arab nations) | Low-Context Cultures (e.g., USA, Germany, Scandinavia) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Value | Harmony (和 - wa in Japan), Group Orientation | Honesty, Individualism, Efficiency |

| Communication Style | Indirect, implicit, relies on non-verbal cues and shared understanding. | Direct, explicit, relies on verbal clarity. |

| Politeness Focus | Positive Politeness is paramount. Maintaining group harmony and saving others' face is crucial. | Negative Politeness is often sufficient. Clear, direct communication is valued to avoid misunderstanding. |

| Disagreement | Avoided or expressed very indirectly. Direct confrontation is a major threat to social harmony. | Can be direct and seen as a sign of honesty and intellectual engagement. |

| Example: Refusing an Invitation | Japan: "That sounds wonderful, but I have a prior commitment." (A polite, indirect refusal that avoids a direct "no"). China: "I'll try my best to make it." (This is often a polite way of saying "no," as the listener is expected to understand the difficulty). |

USA: "Sorry, I can't make it. Thanks for asking!" (More direct and clear). Germany: "Nein, danke. Ich habe andere Pläne." (A direct "No, thank you" is common and not considered rude). |

Case Study 1: English vs. Japanese

-

Requests:

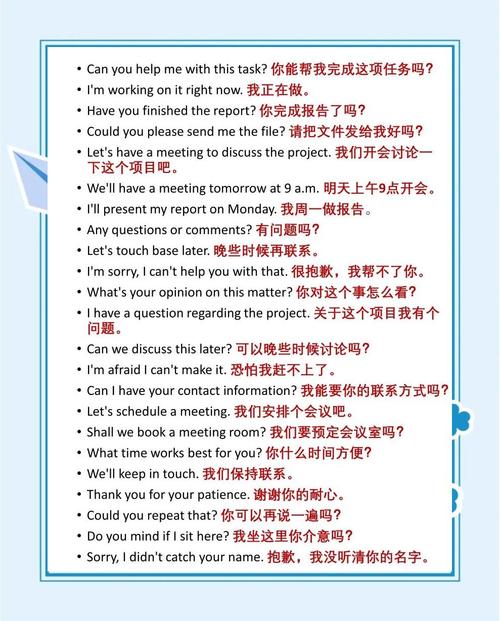

- English: Relies heavily on negative politeness. "Could you possibly...", "Would you mind if I...", "I was wondering if you could..." These phrases explicitly acknowledge the imposition.

- Japanese: Relies more on positive politeness and context. A simple "Sumimasen" (Excuse me/Sorry) can precede a request to show humility and consideration. The level of formality (using keigo - honorific language) is crucial for showing respect.

-

Apologies:

- English: "I'm sorry" is used for both minor inconveniences ("Sorry to bother you") and serious offenses.

- Japanese: "Gomen nasai" is for minor issues. For serious matters, "Moushiwake arimasen" (There is no excuse) or "Sumimasen" (with a deep bow) is used to show deep remorse and a desire to restore the relationship.

Case Study 2: English vs. German

- Directness vs. Indirectness:

- English (especially American English): Tends to use more off-record strategies to soften requests and disagreements (e.g., "I was kind of hoping we could...").

- German: Values directness as a sign of clarity and respect. Beating around the bush can be seen as inefficient or even deceptive. A direct "Nein" (No) is often expected and respected.

Part 3: Research Methodologies in Politeness Studies

Scholars use various methods to study politeness empirically.

- Discourse Completion Task (DCT): A common experimental method. Participants are given a scenario (e.g., "You need to ask a professor for a letter of recommendation") and asked to write down what they would say. This helps collect data on preferred phrases in specific contexts.

- Conversation Analysis (CA): Analyzes naturally occurring, recorded conversations to see how politeness is managed in real-time through turn-taking, pauses, and lexical choices.

- Ethnographic Fieldwork: Researchers immerse themselves in a culture to observe and document politeness norms in their natural setting, providing rich, qualitative data.

- Corpus Linguistics: Uses large databases of spoken and written language (e.g., the British National Corpus) to analyze the frequency and distribution of polite expressions (e.g., "please," "thank you," "sorry") across different genres and speakers.

Part 4: Practical Implications

Understanding politeness differences is crucial in many areas:

- Business and International Relations: Misunderstandings can lead to failed negotiations or damaged relationships. Knowing when to be direct or indirect is key to effective cross-cultural business communication.

- Second Language Acquisition: Learners who only translate politeness formulas from their native language often sound rude or overly formal. Teaching the pragmatic rules of politeness is as important as teaching grammar.

- Diplomacy and Politics: Diplomatic language is a masterclass in off-record and positive politeness, designed to convey strong messages without causing a public face-threatening event.

- AI and Chatbot Design: To make AI assistants more "human-like," they must be programmed with culturally appropriate politeness strategies. A German user might prefer a direct answer, while a Japanese user might find a more deferential and indirect response more helpful.

Conclusion

Politeness is not a universal set of rules but a culturally specific system for managing social relationships. While Brown and Leech's theories provide a valuable analytical framework, the application of these strategies varies dramatically. High-context cultures prioritize group harmony and positive face, often using indirectness, while low-context cultures value clarity and individualism, often favoring directness. A comparative study of politeness reveals that what is considered "rude" in one culture may be "polite" in another. Therefore, the key to effective cross-cultural communication lies not in judging one system as superior, but in developing a deep, empathetic understanding of the underlying cultural values that shape linguistic behavior.